Thursday, October 31, 2013

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

How did ancient Greek music sound?

The music of ancient Greece, unheard for thousands of years, is being brought back to life by Armand D'Angour, a musician and tutor in classics at Oxford University. He describes what his research is discovering.

"Suppose that 2,500 years from now all that survived of the Beatles songs were a few of the lyrics, and all that remained of Mozart and Verdi's operas were the words and not the music.

Imagine if we could then reconstruct the music, rediscover the instruments that played them, and hear the words once again in their proper setting, how exciting that would be.

This is about to happen with the classic texts of ancient Greece.

It is often forgotten that the writings at the root of Western literature - the epics of Homer, the love-poems of Sappho, the tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides - were all, originally, music.

Dating from around 750 to 400 BC, they were composed to be sung in whole or part to the accompaniment of the lyre, reed-pipes, and percussion instruments.

Finding the pitch

But isn't the music lost beyond recovery? The answer is no. The rhythms - perhaps the most important aspect of music - are preserved in the words themselves, in the patterns of long and short syllables.

The instruments are known from descriptions, paintings and archaeological remains, which allow us to establish the timbres and range of pitches they produced.

And now, new revelations about ancient Greek music have emerged from a few dozen ancient documents inscribed with a vocal notation devised around 450 BC, consisting of alphabetic letters and signs placed above the vowels of the Greek words.

The Greeks had worked out the mathematical ratios of musical intervals - an octave is 2:1, a fifth 3:2, a fourth 4:3, and so on.

The notation gives an accurate indication of relative pitch: letter A at the top of the scale, for instance, represents a musical note a fifth higher than N halfway down the alphabet. Absolute pitch can be worked out from the vocal ranges required to sing the surviving tunes.

While the documents, found on stone in Greece and papyrus in Egypt, have long been known to classicists - some were published as early as 1581 - in recent decades they have been augmented by new finds. Dating from around 300 BC to 300 AD, these fragments offer us a clearer view than ever before of the music of ancient Greece.

The research project that I have embarked on, funded by the British Academy, has the aim of bringing this music back to life.

Folk music

But it is important to realise that ancient rhythmical and melodic norms were different from our own.

We must set aside our Western preconceptions. A better parallel is non-Western folk traditions, such as those of India and the Middle East.

Instrumental practices that derive from ancient Greek traditions still survive in areas of Sardinia and Turkey, and give us an insight into the sounds and techniques that created the experience of music in ancient times.

So what did Greek music sound like?

Some of the surviving melodies are immediately attractive to a modern ear. One complete piece, inscribed on a marble column and dating from around 200 AD, is a haunting short song of four lines composed by Seikilos. The words of the song may be translated:

While you're alive, shine:

never let your mood decline.

We've a brief span of life to spend:

Time necessitates an end.

The notation is unequivocal. It marks a regular rhythmic beat, and indicates a very important principle of ancient composition.

In ancient Greek the voice went up in pitch on certain syllables and fell on others (the accents of ancient Greek indicate pitch, not stress). The contours of the melody follow those pitches here, and fairly consistently in all the documents.

Tuning up

But one shouldn't assume that the Greeks' idea of tuning was identical to ours. Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD provides precise mathematical ratios for numerous different scale-tunings, including one that he says sounds "foreign and homespun".

Dr David Creese of the University of Newcastle has constructed an eight-string "canon" (a zither-like instrument) with movable bridges.

When he plays two versions of the Seikilos tune using Ptolemy's tunings, the second immediately strikes us as exotic, more like Middle Eastern than Western music.

The earliest musical document that survives preserves a few bars of sung music from a play, Orestes by the fifth-century BC tragedian Euripides. It may even be music Euripides himself wrote.

Music of this period used subtle intervals such as quarter-tones. We also find that the melody doesn't conform to the word pitches at all.

Euripides was a notoriously avant-garde composer, and this indicates one of the ways in which his music was heard to be wildly modern: it violated the long-held norms of Greek folk singing by neglecting word-pitch.

However, we can recognise that Euripides adopted another principle. The words "I lament" and "I beseech" are set to a falling, mournful-sounding cadence; and when the singer says "my heart leaps wildly", the melody leaps as well. This was ancient Greek soundtrack music.

And it was received with great excitement in the Greek world. The historian Plutarch tells a moving story about the thousands of Athenian soldiers held prisoner in roasting Syracusan quarries after a disastrous campaign in 413 BC. Those few who were able to sing Euripides' latest songs were able to earn some food and drink.

What about the greatest of ancient poet-singers, Homer himself?

Homer tells us that bards of his period sang to a four-stringed lyre, called a "phorminx". Those strings will probably have been tuned to the four notes that survived at the core of the later Greek scale systems.

Professor Martin West of Oxford has reconstructed the singing of Homer on that basis. The result is a fairly monotonous tune, which probably explains why the tradition of Homeric recitation without melody emerged from what was originally a sung composition.

"What song the Sirens sang," is the first of the questions listed by the 17th Century English writer, Sir Thomas Browne, as "puzzling, though not beyond all conjecture".

"The reconstruction of ancient Greek music is bringing us a step closer to answering the question."

Friday, October 25, 2013

Hamilton de Holanda e Stefano Bollani

Stefano Bollani (born 5 December 1972, Milan) is an Italian jazz pianist from Milan.

He made his professional debut at fifteen and received his diploma in piano from the Conservatorio Luigi Cherubini in Florence. He performs classical music, smooth jazz, avant-garde jazz, Brazilian jazz, and pop rock. In 1998, Musica Jazz magazine voted him Best Jazz Talent of the Year and later he would be awarded for jazz by a New Swing group in Japan. While he is mostly known for his collaborations with Enrico Rava, he has made several albums as a leader, and has been favourably acknowledged by several long established jazz musicians, such as Martial Solal. The album Mi ritorni in mente, includes an interpretation of the standard "Nature Boy" which has been acclaimed by many.

He is married to the Italian singer Petra Magoni.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Rob Mazurek & São Paulo Underground in Athens

23-24 Οκτωβρίου 2013

Στέγη Γραμμάτων και Τεχνών

21:00 Μικρή Σκηνή

Μουσική μέσα από ένα βιογραφικό: Ο Αμερικανός κορνετίστας Rob Mazurek γεννήθηκε το 1965 στο Τζέρσεϋ Σίτυ (ροκ, τζαζ, μπλουζ, hard-bop), μεγάλωσε στα περίχωρα του Σικάγου (σύγχρονη πρωτοπορία, electronica, indie rock, μινιμαλισμός, πειραματικά), ενώ από το 2000 ζει στη Βραζιλία (samba, bossa nova, maracatu, πολυρρυθμίες). Συνεργαζόμενος από τότε με τον –τριαντάχρονο σήμερα– περκασιονίστα Mauricio Takara, καθώς και με τον πολυοργανίστα Guilherme Granado, δημιουργούν ένα εκρηκτικό κοκταίηλ όλων αυτών των ακουσμάτων, με πρόσθετες δόσεις ψυχεδέλειας, ποπ-ροκ εφευρετικότητας, ήχων του δρόμου, συγκοπτόμενων ρυθμών ή επιρροών από τον «διαστημικό» Sun Ra και τον δάσκαλο του Μαζούρεκ, Art Farmer, έναν bebop θρύλο. Το ακουστικό αποτέλεσμα των São Paulo Underground είναι προϊόν ζύμωσης αντιθέσεων μιας παλέτας όπου η τραχύτητα και η ευφορία συνδιαλέγονται σε ένα σαγηνευτικά αχανές ψηφιδωτό το οποίο, εντέχνως, αφήνει διψασμένο τον ακροατή να θέλει περισσότερα…

Πολυσυλλεκτική πράξη με δάνεια από λατινοαμερικάνικα ριφ, post-bop αρμονίες, αλλά και συνθέματα της μίας συγχορδίας. Εκρήξεις ζωτικότητας, ambient σύννεφα, αναφορές σε χορευτικούς ρυθμούς, ρέγκε περάσματα, free-jazz «ζούγκλες» ή υπερρεαλιστικά ηχογεγονότα. Υλικό επεξεργασμένο ή αυθόρμητο, βίαιος έως ντελικάτος χάλκινος ήχος ανάμεσα στους Miles Davis και Don Cherry, σε μία, χωρίς προηγούμενο, νέα βραζιλιάνικη οπτική.

Rob Mazurek: κορνέτα, electronics

Guilherme Granado: πλήκτρα, samplers, φωνή

Mauricio Takara: ντραμς, cavaquinho, electronics

Διαβάστε περισσότερα:

• Από τις δεκάδες συνεργασίες του Μαζούρεκ ξεχωρίζουν αυτές με τους Pharoah Sanders, Roscoe Mitchell, Yusef Lateef, Nana Vasconcelos, Bill Dixon, αλλά και με τον Jim O’ Rourke, τους Tortoise και τους Stereolab.

• O Μαζούρεκ, που είναι επίσης ζωγράφος και video-artist, έχει ταξιδέψει πολύ με όλες αυτές τις ιδιότητές του (Ασία, Αμερική, Ευρώπη). Έχει δεχτεί παραγγελίες και έχει συνθέσει έργα για φορείς και φεστιβάλ στην Ιταλία και τις ΗΠΑ. Συνολικά έχει πραγματοποιήσει ηχογραφήσεις με περισσότερες από 200 πρωτότυπες συνθέσεις. Έχει μια μόνιμη διάθεση χιούμορ, όπως μαρτυρά και ο τίτλος του δίσκου Tres Caberas Loucouras, δηλαδή «Τρία Παλαβά Κεφάλια»…

• Βάση των São Paulo Underground είναι η χημεία μεταξύ του Μαζούρεκ και του Τακάρα. Γέννημα-θρέμμα Παουλίστας (όπως ονομάζονται οι κάτοικοι του Σάο Πάουλο) και πρώην hardcore punk ντράμμερ, ο Μαουρίτσιο Τακάρα αγαπάει επίσης το καβακίνιο, ένα μικρό παραδοσιακό βραζιλιάνικο κιθαρόνι.

• Εκτός από φίλοι και συνεργάτες, οι τρεις μουσικοί είναι και κουμπάροι! Το 2012 οι Τακάρα και Γρανάδο πάντρεψαν τον Μαζούρεκ με την εκλεκτή της καρδιάς του!

The Cover Art of Blue Note Records

The Blue Note design team of Francis Wolf and Reid Miles defined much of the Jazz and Beatnik aesthetic and had a profound effect on post war graphics and design. This book demonstrates their ethos of clean lines, quirky typography, amazing uses of geometry and shapes and the coolest of photography - particularly the black and white work.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

How To Sing: Lilli Lehmann’s Illustrated Guide (1902)

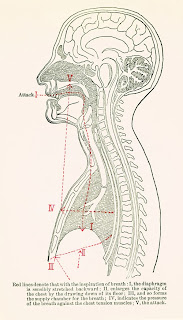

Just like learning to listen to music is an acquired skill, learning to make music may have as much to do with discipline and practice as it does with inborn “talent,” if not more. In How To Sing (public library; public domain), originally published in 1902, German opera superstar Lilli Lehmann sets out “to discuss simply, intelligibly, yet from a scientific point of view, the sensations known to us in singing” by exploring “the expressions ‘singing open,’ ‘covered,’ ‘dark,’ ‘nasal,’ ‘in the head,’ or ‘in the neck,’ ‘forward’ or ‘back.’” But more than a mere technical guide to vocal skill, Lehmann’s treatise is really a guide to thinking musically and a dimensional meditation on the general art of learning. Equally enchanting are the anatomical diagrams — an inadvertent recurring theme around here lately — illustrating her theories.

Lehmann begins with an articulate assertion about the osmosis of nature and nurture:

"The true art of song has always been possessed and will always be possessed by such individuals as are dowered by nature with all that is needful for it — that is, healthy vocal organs, uninjured by vicious habits of speech; a good ear, a talent for singing, intelligence, industry, and energy."

She stresses the responsibilities of students and teachers:

"One is never done with learning. … Learning and teaching to hear is the first task of both pupil and teacher. One is impossible without the other. It is the most difficult as well as the most grateful task, and it is the only way to reach perfection."

Lehmann goes on to delineate a number of technical and strikingly specific recommendations for singing, such as:

"The singer’s endeavors, consequently, must be directed to keeping the breath as long as possible sounding and vibrating not only forward but back in the mouth, since the resonance of the tone is spread upon and above the entire palate, extends from the front teeth to the wall of the throat. He must concern himself with preparing for the vibrations, pliantly and with mobility, a powerful, elastic, almost floating envelope, which must be filled entirely, with the help of a continuous vocal mixture, — a mixture of which the components are indistinguishable."

Lehmann goes on to extol The Great Scale, noting:

"This is the most necessary exercise for all kinds of voices. It was taught to my mother; she taught it to all her pupils and to us. But I am probably the only one of them all who practices it faithfully! I do not trust the others. As a pupil one must practice it twice a day, as a professional singer at least once.

The scale must be practiced without too strenuous exertion, but not without power, gradually extending over the entire compass of the voice; and that is, if it is to be perfect, over a compass of two octaves. These two octaves will have been covered, when, advancing the starting-point by semitones, the scale has been carried up through an entire octave. So much every voice can finally accomplish, even if the high notes must be very feeble.

The great scale, properly elaborated in practice, accomplishes wonders: it equalizes the voice, makes it flexible and noble, gives strength to all weak places, operates to repair all faults and breaks that exist, and controls the voice to the very heart. Nothing escapes it."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)