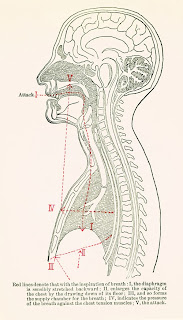

Just like learning to listen to music is an acquired skill, learning to make music may have as much to do with discipline and practice as it does with inborn “talent,” if not more. In How To Sing (public library; public domain), originally published in 1902, German opera superstar Lilli Lehmann sets out “to discuss simply, intelligibly, yet from a scientific point of view, the sensations known to us in singing” by exploring “the expressions ‘singing open,’ ‘covered,’ ‘dark,’ ‘nasal,’ ‘in the head,’ or ‘in the neck,’ ‘forward’ or ‘back.’” But more than a mere technical guide to vocal skill, Lehmann’s treatise is really a guide to thinking musically and a dimensional meditation on the general art of learning. Equally enchanting are the anatomical diagrams — an inadvertent recurring theme around here lately — illustrating her theories.

Lehmann begins with an articulate assertion about the osmosis of nature and nurture:

"The true art of song has always been possessed and will always be possessed by such individuals as are dowered by nature with all that is needful for it — that is, healthy vocal organs, uninjured by vicious habits of speech; a good ear, a talent for singing, intelligence, industry, and energy."

She stresses the responsibilities of students and teachers:

"One is never done with learning. … Learning and teaching to hear is the first task of both pupil and teacher. One is impossible without the other. It is the most difficult as well as the most grateful task, and it is the only way to reach perfection."

Lehmann goes on to delineate a number of technical and strikingly specific recommendations for singing, such as:

"The singer’s endeavors, consequently, must be directed to keeping the breath as long as possible sounding and vibrating not only forward but back in the mouth, since the resonance of the tone is spread upon and above the entire palate, extends from the front teeth to the wall of the throat. He must concern himself with preparing for the vibrations, pliantly and with mobility, a powerful, elastic, almost floating envelope, which must be filled entirely, with the help of a continuous vocal mixture, — a mixture of which the components are indistinguishable."

Lehmann goes on to extol The Great Scale, noting:

"This is the most necessary exercise for all kinds of voices. It was taught to my mother; she taught it to all her pupils and to us. But I am probably the only one of them all who practices it faithfully! I do not trust the others. As a pupil one must practice it twice a day, as a professional singer at least once.

The scale must be practiced without too strenuous exertion, but not without power, gradually extending over the entire compass of the voice; and that is, if it is to be perfect, over a compass of two octaves. These two octaves will have been covered, when, advancing the starting-point by semitones, the scale has been carried up through an entire octave. So much every voice can finally accomplish, even if the high notes must be very feeble.

The great scale, properly elaborated in practice, accomplishes wonders: it equalizes the voice, makes it flexible and noble, gives strength to all weak places, operates to repair all faults and breaks that exist, and controls the voice to the very heart. Nothing escapes it."

No comments:

Post a Comment